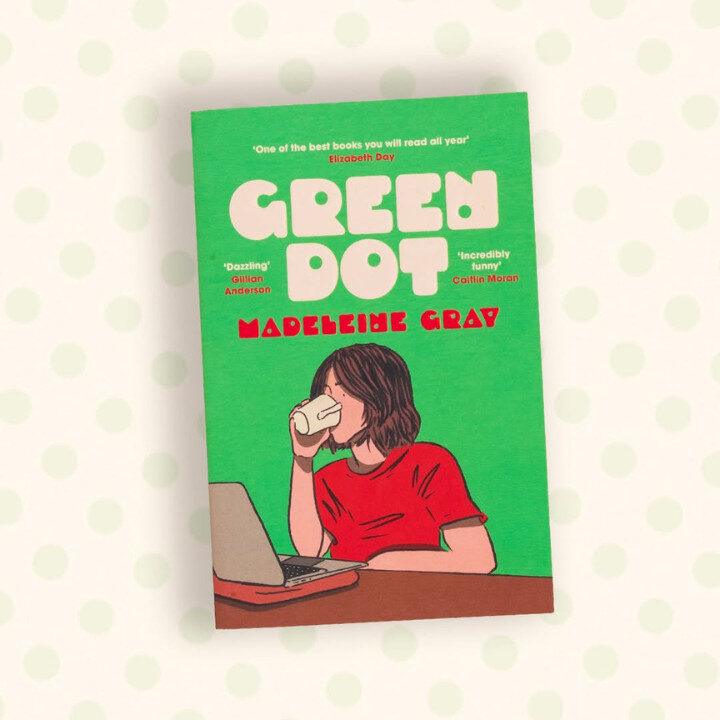

Ever since the release of her debut novel ‘Green Dot,’ Madeleine Gray has been sparking discussions – her work resonating with readers who are deeply moved by its exploration of love and self-identity. When she visited Hong Kong for the International Literary Festival, Madeleine sat down with us to talk about the emotional complexity of her protagonist, Hera, and how the novel has impacted the literary community. With rave reviews and a film adaptation already in the works, ‘Green Dot’ has proven to be more than just a book – it’s a conversation starter, especially in a world where connection and disconnection seem to coexist in equal measure.

Read More: This International Women’s Day, These Female Heroes Deserve The Spotlight

Lockdown changed so many lives, including yours. How did the silence of that time help you hear your inner voice more clearly?

When lockdown began, I was living in Manchester, doing my PhD in literary theory. The UK lockdowns were intense, with only 45 minutes outside per day. I didn’t have much of a support system there, and it was a really dark time. I found myself going to places in my head that weren’t healthy. A few months in, I decided to return to Sydney, which I’d been avoiding for years. Coming back, I realised I appreciated it more than ever – family was here, and I was closer to the beach and the sunshine. It was a relief.

I continued my PhD remotely, which could have been isolating, but two things happened. First, I started working part-time at a bookstore that managed to stay open because it sold stationery. This was vital for me. Working alongside coworkers who were going through similar challenges was empowering. We were young people, just trying to make the best of a tough situation. During that time, we also started unionising the bookstore because of underpaid workers. It gave us a sense of agency when so much was being taken from us.

This experience gave me the confidence to start writing fiction. I had been writing academic criticism but never thought I had a story worth telling. Unionising during lockdown, however, boosted my confidence. The isolation – combined with living alone – left me with time to write, and every time I returned from the bookstore, the words just poured out of me. Writing became my way of connecting with myself when I couldn’t see anyone else, and that’s how my novel was born – written as a dialogue with myself to stave off madness during lockdown.

Can you talk about the inspiration behind Hera and how you intended for readers to empathise with her, despite her flawed choices?

I’ve spent a lot of time writing literary criticism and developing my own take on the subgenre of intergenerational affair novels. There are many contemporary stories where a younger woman has an affair with an older, usually married man. I’ve always found this dynamic fascinating because affairs carry so much moral stigma and secrecy, yet there’s also desire and danger surrounding them. I wanted to explore why a young, educated woman, with her own career and independence, would still choose to have an affair with a married man.

For Hera, my protagonist, she sees Arthur, a 40-year-old man, as a way to find happiness. At 24, she feels lost and unsettled, and Arthur represents stability: a man who has his life together with a job and a mortgage. She wants that, but also feels guilty for desiring it, given her education and feminist beliefs. She’s constantly grappling with her self-loathing and the realisation that she shouldn’t define happiness through a man.

Given that Hera is the “other woman,” I knew readers might initially detest her. After all, her actions are seen as morally repugnant. That’s why I wrote the book in the first person – so readers could enter her mind and understand why she would continue down this self-sabotaging path. I wanted to explore how far we’ll go when we’re in love – a theme that is universally relatable, but in the specific context of an intergenerational affair.

And just to clarify – no, I didn’t have an affair with a married man. But I’ve had relationships that were disappointingly one-sided, where you pour so much into something that just isn’t right. My friends have had similar experiences, and I wanted to explore that feeling of being trapped in a cycle of hope, despite knowing better.

What inspired you to reimagine the classic “other woman” trope by layering it with elements of queerness? It’s not something we see often.

I’m glad you asked. Most of the novels I’ve read feature heterosexual women with heterosexual men. But for Hera, she’s queer and bisexual. Before meeting Arthur, she had only been in relationships with women. As a queer person, I wanted to see that kind of representation, both for myself and for the story. Hera comes to heteronormative tropes later than most people, especially compared to characters in the books I read, where straight people are conditioned into these roles from a young age, often through high school relationships. Hera hasn’t learned these roles because she’s been with women.

When she’s with Arthur, she’s unsure whether gender differences are simply because he’s a man, or if it’s part of the affair dynamic. There’s a tension where she’s somewhat naïve, but her queerness gives her an ironic distance from the situation. She’s aware of gender studies, of theorists like Eve Sedgwick, and knows what heteronormativity is. Yet, she’s playing a role that goes against everything she ideologically believes. I wanted to explore how, even when we have the language to describe something as wrong ideologically, it doesn’t mean we don’t still want it. Hera epitomises this struggle. It’s very human, and it made me connect with her character much more.

What do you hope readers take away from Hera’s experience, especially in terms of love and self-identity?

I hope readers see it as a cautionary tale about how you can’t build your identity by becoming an extension of someone else. You have to cultivate your sense of self independently. I’ve been asked what I hope happens to Hera after the book ends, and my hope is that she finds happiness and fulfillment that doesn’t depend on anyone else. Relationships and connections are important, but they should enhance your life, not define it. If they were taken away, you should still be able to stand on your own.

How did you ensure the story felt both fresh and brutally honest about the realities of modern relationships?

The book is peppered with pop culture references – Desperate Housewives, Lizzo, Phoebe Bridgers – things that Hera and her friends relate to. They speak in references, which I think many people our age do. It worked well because Arthur, from a different generation, has his own set of references. I think a lot of love is about translating what’s in your head to someone else’s. The intimacy comes when you exchange and mix those references – it’s something I find really intimate.

‘Green Dot’ really captures the mood and language of Gen Z. What do you think are the defining characteristics of this generation?

A big influence for me was working at the bookstore while I was writing. I was the oldest colleague there at 27, and I learned a lot from my younger coworkers – especially the way they communicated. What struck me, and also made me a bit sad, was that when I was growing up, there was this earnest belief in progress – that we could change political systems, solve climate change, and make things better. My younger colleagues, though, have grown up with access to the internet and information, and they’ve developed a more sardonic, distrustful view of institutions. I don’t think this is a bad thing – it’s actually healthy to question institutions – but it’s different from the innocence my generation had. Gen Z has this ironic distance and cynicism, which really permeates characters like Hera and her friends. I think she embodies those elements perfectly.

What do you want to explore more in your future writing? Is there something you’ve touched on here that you want to dive deeper into, whether in your next novel or in future academic work?

You’ve caught me at an exciting time, actually – I just sold my second novel! This new book focuses more on female friendship. The core relationship is between two women over a long period of time, exploring the intimacy and sometimes painful dynamics of how we can hurt those we love, particularly when they’re like family. We all have friendships like that, where we know we can hurt each other but still be loved.

I also want to delve deeper into motherhood. Since writing ‘Green Dot,’ I’ve become a stepmother to a four-year-old, which has opened up a whole new way of thinking about what it means to be responsible for another life. It’s humbling, and it’s made me respect all parents even more.

Lastly, while ‘Green Dot’ touches on Hera’s queerness, I want to explore female queerness more explicitly in my next book. This one is really, really gay.

Follow Madeleine Gray on Instagram to stay updated on her latest work.

Catherine Pun

A Hong Kong native with Filipino-Chinese roots, Catherine infuses every part of her life with zest, whether she’s belting out karaoke tunes or exploring off-the-beaten-path destinations. Her downtime often includes unwinding with Netflix and indulging in a 10-step skincare routine. As the Editorial Director of Friday Club., Catherine brings her wealth of experience from major publishing houses, where she refined her craft and even authored a book. Her sharp editorial insight makes her a dynamic force, always on the lookout for the next compelling narrative.